- Home

- Anna Mehler Paperny

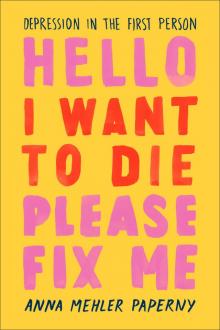

Hello I Want to Die Please Fix Me Page 3

Hello I Want to Die Please Fix Me Read online

Page 3

At night her moans of discomfort roused me from whatever light doze I could manage, till I prayed for one or both of us to just shut up and die. In the morning, remorse at my murderous callousness prompted me to slip her, at her request, the packets of salt from my meal tray—she got none, for health reasons. Was I undermining her long-term wellness? Maybe. But when you’re old and alone and in pain and stuck in hospital after trying to slit your wrist, surely there are more important things to worry about than sodium intake.

A nurse-chaperoned trip down to the hospital’s belly for a brain scan felt like a vacation. I spent interminable minutes in a luminescent white Space Odyssey cocoon whose broad vocabulary of echoing blurps and bloops mimicked the sound effects of a retro sci-fi film. I learned the less-than-uplifting result of this diversion days later. An otherworldly neurologist—wide blue eyes growing wider, syncopated Scandinavian-accented voice slowing as she spoke—walked me through a series of white blobs I was told depicted my brain.

A dangly blob at the centre of the bird’s-eye image she introduced to me as my putamen, located near the bottom of the brain itself. It was swollen thanks to the antifreeze I’d swallowed. I learned through later googling that, once in your system, the methanol in antifreeze metabolizes into formic acid, which can prevent your cells from grabbing and using the oxygen they need, ultimately killing you within about thirty-six hours.6 Your optic nerve and basal ganglia are among the first bodily bits badly damaged in this process—either directly poisoned by formic acid or suffocated by lack of oxygen. Depending how badly damaged they are, you could be blind or shaky and off-balance for the rest of your life. I did not know this when I gulped that blue liquid. My pre-attempt googling fixated only on the prospect of death, not debilitation. I’d gone for what seemed both efficacious and accessible, with little thought for side effects. Smart!

I was unreasonably lucky, the neurologist told me, in a tone that suggested I should not tempt fate again: the damage to my basal ganglia was probably temporary, she advised. (She also advised me to avoid booze for the next several months. What, you mean other than methyl alcohol?) That swollen dangly blob, my putamen, explained my greater-than-usual klutziness; a damaged optic nerve could explain the watery stinging in my eyes every time I tried to focus. My swollen putamen also sabotaged my hands when I needed them most. For weeks I wrote and typed with agonizing, disorienting slowness, cramped fingers and crabbed letters not my own.

That panicky self-alienation dissipated after a couple of months, and by January follow-up brain scans found my putamen had recovered as much as it ever will. I discovered soon after that I could no longer pull off high heels when I toppled over like a drunken pygmy giraffe while walking fifty metres to a wedding venue. Red-faced and mortified I picked myself up, cradling my miraculously unshattered camera and avoiding eye contact, slunk back to the vehicle I’d carpooled in to retrieve a pair of flat sandals. (For the record, I temporarily relearned how to walk in heels for my baby brother’s 2017 wedding and remain absurdly proud of myself for not sprawling across the aisle or crushing small children on the dance floor.) Some necrotic-looking scar tissue remains, nerve fibres stripped of their white myelin insulation. Insidious symptoms persist: I still get freaky limb microtremors, jackhammer legs, shaky hands that shake more thanks to certain psychotropic medications I’ve taken on and off for the past several years. Three-and-a-half years later, back in hospital following—SPOILER ALERT—another suicide attempt, a bemused doctor approached my ICU bed, scans in hand, wondering how a woman in her late twenties had the brain of a stroke victim. That’s apparently what medical images of my brain look like to people who aren’t expecting to encounter methanol’s neurological souvenirs.

Back in the psych ward, I was acutely aware of my involuntary status and irrationally resentful of anyone there with me who was effectively free to go at any time. A young bearded man who’d voluntarily checked himself in to the short-term psych ward spent extensive amounts of time on the hospital phone talking about how he’d just needed some time to decompress, you know? He held forth at length on the quality and quantity of food he consumed and its variegated effects on his digestive system. It’s vital for voluntary admission to be available to people in crisis—it’s infinitely better than the alternative, of resources being unavailable or only available on an involuntary basis. But goddamn, I was so jealous.

Form 3 or no, I was sure if I just acted normal enough they would let me go. I tried to be courteous, lucid and calm but not suspiciously upbeat. I didn’t weep or scream at my own frustration or impotence or exhaustion or insomnia or self-loathing. I met, as required, multiple times a day with nurses and social workers. And my I’m-totally-fine, suicide-was-a-one-time-aberration ploy almost worked: I was almost set free by the first psychiatrist I saw within a week of my admission without so much as a follow-up appointment.

I admit we got off on the wrong foot with that first psychiatrist. This could be because my family and I misjudged her appetite for jokes. The six of us—me, parents, siblings, psychiatrist—had a painful group session involving questions about not just me but family practices and dynamics. (I learned later on that my parents, as family members grasping for information and a meaningful sense of participation in their loved one’s care, found this group session more useful than I did.) When substance use came up I recall my dad saying something along the lines of, “Do we drink? Oh, yeah. Allllll the time.” And then we all chuckled while the psychiatrist sat stony-faced and made notes that, I later learned, branded us all alcoholics. Let me be clear: my family drinks regularly, especially when together. But none of us drink destructively. We don’t get antsy-distressed when we go without booze. Clearly this is something I should have paused our psych-session wisecracking to clarify before the woman pathologized us all.

Anyway.

My discharge was scheduled, it shone like a beacon, with nothing more for me to deal with than a list of phone numbers of private pricey psychotherapists and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, whose wait list for a publicly covered post-suicide psychiatric consultation stretched past six weeks. I dutifully made these calls from behind my blue curtain, voice comically lowered as I shamefully booked appointments with several psychotherapists I hoped my employer would pay for even as I recoiled from the idea of couch-bound confessions, knowing I’d distance myself from everything to do with this horrid experience as soon as possible.

Incidentally, discharging inpatients who have mental disorders requiring ongoing treatment with a series of phone numbers and a pat on the head is not considered best practice: it’s a great way to ensure people fall through the cracks and (if they’re lucky) wind up back in hospital in worse shape than before. St Joe’s, the hospital where I stayed, now has a mental health outpatient clinic that focuses in part on catching people at risk of death or deterioration as they head back into the community. Hooking people up with ongoing care, making the transition as seamless as possible, makes for better outcomes—and, hopefully, fewer fatally shitty ones. Yet somehow ensuring smooth psych transitions remains the exception, not the rule. It’s a hospital-dependent crapshoot.

My parents—who’d been driven nuts by the sense of enforced helplessness and ignorance they had to live with as family members of mental patients who by law retain their right to privacy—thought setting me free less than a week after a suicide attempt was a bad idea. We had a bruising shouting match, pacing back and forth in sinking damp sand by Lake Ontario, near the path we walked during my all-too-brief afternoon chaperoned psych-ward reprieves, arguing over whether I should live with them in Vancouver on my release. I wanted to go home to my apartment. But I admit my argument was less than compelling:

“I’m fine!”

“That’s what you said before you tried to kill yourself.”

“But now I really am fine!”

My parents won that argument, albeit not in the way they—or I—expected.

3

Psych-Ward S

ojourn

Unbeknownst to me, as I paced by my bed and prepared for life outside the windowless ward, my parents had pushed for a second opinion, my dad writing desperate, pleading emails at three o’clock in the morning. And they got one.

The second psychiatrist was smart and sardonic and treated me like someone capable of communicating in multisyllabic sentences. He also had a far better bullshit-detector. He did not buy my argument that this whole suicide thing was an anomalous one-off, a mental misunderstanding, never to recur. He decided I had major depression. And that I was fucked-up enough to merit more time locked up lest I try to off myself again.

So much for my “suicide, shmuicide” master plan. The people charged with keeping me alive were not so easily convinced.

Years later I still resent his decision to keep me locked up, even though his intervention also earned me invaluable outpatient care and years of life-ameliorating, arguably lifesaving treatment. He also got me started on meds, the beginning of a years-long pill-popping parade, on which more later. This was the doctor I would see as an outpatient, who would help me stay alive in the most basic way for years. But I still don’t think I needed more time in a mental institution—I think I could have started one-on-one outpatient pharmaco- and psychotherapy sooner and skipped the extra time in the ward and gotten more benefit from it without risking another self-administered death. He still contends that keeping me in a psych ward was the right move because I was at a high risk of attempting suicide after what he concluded was a serious and premeditated attempt—apartments don’t get to that state in a day, and telling him gulping antifreeze was a freak impulsive act “would have been a whole lot easier to argue if you drove a car,” he said. My attempt at a model-patient persona was not how people who attempted suicide on impulse tend to act. Letting me go at that point “would have been a premature discharge.” And premature discharges in all contexts are of course to be avoided.

But at the time I just about broke down. Agape as my discharge—which was scheduled, which I’d prepped for—was delayed, I struggled to process the prospect of more time without freedom of movement, more sleepless hospital nights. I squandered precious visiting hours pacing the three-step space along my bed. In hindsight I can see it seems an overreaction but at the time I was distraught, unable to bear the company of loved ones who could come and go as they chose.

Within hours of my getting the unwelcome news, a well-meaning patient advocate whose business card I promptly lost took me aside and explained I could appeal, if I wanted, to the Consent and Capacity Board. That board, he explained, made up of psychiatrists, lawyers and laypersons, is where you go when there’s a disagreement over how crazy you are or who should get to decide on treatment if a patient herself can’t. I later found its caseload more than doubled in the decade ending in 2016–17:1 the biggest portion of its applications (46 percent in 2016–17) dealing with patients’ involuntary status. The onus is on the attending doctor, the one who put you on the Form, to prove you should be there. I spent a day considering trying to challenge my commitment. By this time I’d been in hospital just over a week, but I still hoped somehow good behaviour would earn me a clean bill of health and quicker return to the newsroom. (Also, by then I’d lost that guy’s card.)

So I got myself set to move to the long-term psych ward upstairs. I packed the too many belongings I’d accumulated—books and clothes, but also the rosemary plant from my mother, the stuffed monster and fuzzy slippers from friends—into too few plastic bags. With a nurse at my side I trekked upstairs, looking every bit a dishevelled bag lady—a parody of a poor soul who belongs somewhere closed off and sedated.

* * *

—

THE SEVENTH-FLOOR PSYCH WARD—7M, it’s called—was a converted brick-gabled nunnery at the top of the hospital. And I will give it this: it had a lovely view, catching morning sun and evening sun and the glinting, traffic-rimmed Lake Ontario to the south. I got a chance to admire this view for the first time as I fidgeted in the TV alcove while my possessions were taken away and protractedly combed through. I stood by a window near the bland square side table and the unstainable blue-green L-shaped couch, avoiding eye contact with the patients watching TV beside me or reading, sitting and staring, or playing games in the larger adjoining activity room, used breakfast trays stacked in a tall wheeled cart in the corner. They let me keep my shoelaces and earbuds but confiscated spare hair elastics and charger cords, along with the nail polish my younger sister had given me and the jar of apple butter from my mother—part of her ongoing attempt to make my psych-ward sojourn as homey as possible. Unquenchable nesting instinct! Were I on death row or locked in solitary I’m certain she’d bring me a potted plant, yoga mat, prints for the walls or a beach-glass mobile to hang from the ceiling.

The nurse who led me to my latchless, off-white room advised me to keep all my possessions locked for safekeeping in the vertical cupboard to which the nurses kept the key.

“Oh, are many things stolen here?”

“Oh, yes.”

The sureness of her response, that implied inevitability of theft, sparked an immediate suspicion of my fellow inmates. Unwarranted: the only thing anyone ever stole from my room was some fruit.

My quarters resembled, really, a spartan university dorm room: bed, desk, chair, cupboard/wardrobe. On the walls were scrawled disappointingly uncreative rants, much of it written in the same ballpoint pen, mostly combinations of homages to and warnings against Satan. I spent too many time-killing hours engaged in morbid handwriting analysis, comparing the sole pencilled set of rantings to the satanic ballpoint pen. Same person, different implement? Different person, same crazed uncreativity? The myth of the mad creative genius makes for good narratives but in my experience it’s a myth. I know brilliant people who have mental illness but the latter is a bug, not a feature. Psychic torment punches you in the face and crowbars you in the knees; it doesn’t make you Mensa magic. Maybe some lucky nutbars have the productive-creative-brilliant brand of crazy. But the only reason it seems an inordinate number of artsy genius types are crazy is because you never hear from us normal crazy people. All those tortured brainiacs are far outnumbered by poor fuckers who’re just tortured. Mental illness made me incurious, inert. I retreated into myself. I struggled to write. I could not take notes, despite my grandmother’s advice. Even outside hospital, in the months before my first suicide attempt and the years afterward, the deepening of suicidal despair drowned out any creativity or curiosity I thought I had even as I struggled to keep pitching, keep chasing, keep filing. My handwriting’s never been legible but my swollen putamen made my hand muscles seize up and rebel. To see words I’d written sprawl unrecognizable like pulverized mosquitos across a page was terrifying and disorienting and made me even more reluctant to record anything.

The bed was pushed lengthwise against the east-facing window whose lower half, for some reason, was tinted. I caused one poor nurse minor panic when I stood on the bed for a better view of the traffic wormtrails seven storeys below, leaving only part of my torso (The strangulation-by-hanging part, right?) visible from the hallway through the small window in my door. But there were precious few ligature opportunities to be had in that convent enclave. Not that I was actively looking, but it was hard not to think about, a niggling errand you’d rather ignore but that keeps presenting itself, in the same way I joked with Omar about testing the tensile strength of the headphones they let me keep. I really was joking but also wondered—could I use them?

None of the doors locked and they didn’t latch shut properly either—not mine, not the washroom’s, not the shower room’s where the wooden urine-scented bench lent a deceptively sauna-y air of class, as though it belonged in the mountain chateau of a senile, eccentric old man. Showers were a daily failed attempt to put my change of clothes somewhere they wouldn’t get soaked; I wasn’t about to trudge through that hall wearing nothing but a hospital-issued towel.

To enter the ward from the seve

nth-floor elevator you needed to be beeped in by whomever was (wo)manning a nurses’ station beyond the heavy locking glass doors with their “WATCH FOR ELOPEES” sign. No one eloped, or tried to, while I was in that ward. I kept wishing someone would.

The tiled whitish hallway leading to the patient rooms smelled eternally of piss thanks to an incontinent, bedridden, birdlike old lady across from the nurses’ station. The space was nonetheless perpetually teeming with patients milling about or waiting to use the phone or seeking a nurse’s attention. We were each assigned a nurse in the morning, based on who was working that day, names written in blue on a whiteboard like awkward workplace team-building assignments. Each nurse had a handful of inpatient charges and you were supposed to address any concerns/complaints/requests to your designated nurse of the day. Attempting to talk to anyone else elicited a terse “I am not your nurse!” and a quickly receding back. I know you don’t want a bedlam of patients shouting at random people in uniforms. But this felt damn infantilizing.

The doors to everyone’s room were rarely open unless there were nurses inside checking vitals or administering meds or haranguing ambulatory patients out of bed. You’d think a psych ward would be the one place it’s acceptable to stay in bed and wallow in your own misery. But no. Orderlies changed sheets and garbage and, if you caught them at the right time, your towel for a fresh one. One nurse showed me the rumbling industrial washer and dryer down the hall where they washed the linen and where I could do my own laundry. Never before or since has this seemed such a privilege.

Hello I Want to Die Please Fix Me

Hello I Want to Die Please Fix Me